In Hinduism education is an important means to achieve the four aims of human life, namely dharma (virtue), artha (wealth), kama (pleasure) and moksha (liberation). Also, it is vital to the preservation and propagation of Dharma, without which, declares vedic dharma, we cannot regulate our society or families properly or live in peace.

Vidya or education is the means by which an individual can gain right knowledge, control his desires and learn to perform his obligatory duties with a sense of detachment and devotion to God, so that he can overcome the impurities of egoism, attachment and delusion and achieve liberation. In Hindu tradition, an illiterate person is considered to be equal to an animal (pasu), because without education he will not be able to rise above his physical self.

Hence the belief that a person who is initiated into education is twice born, first time physically and second time spiritually. Knowledge is a double edged sword. In the hands of an immoral or evil person it can become a destructive force.

With knowledge comes power and if it falls into the hands of an ill equipped person who is bereft of morality and sense of responsibility, he may misuse the power and bring misery to himself and others. The basic difference between a god and an asura (demon) is that the former uses his knowledge for the welfare of the world and the latter for his own selfish and egoistic aims.

Hence as a part of their education, in ancient India, students were advised to follow the path of gods and cultivate virtue under the careful and personal guidance of their teachers, so that they would remain on the path of righteousness for the rest of their lives and contribute to the welfare of society. The believed that if students were grounded in dharma, they would become its upholders and take care of its survival and continuity

Hindu scriptures recognize two types of knowledge, the lower knowledge and the higher knowledge. Knowledge of the rites and rituals and scholarly study of scriptures is considered to be the lower knowledge, while higher knowledge is the knowledge of Atman and Brahman, gained through personal experience or self realization. Of the two, the higher Knowledge is preferred, because it liberates people from the cycle of births and deaths.

Lower knowledge is often equated with avidya or ignorance because it is acquired through senses and deals with the material aspects of our existence. activeactiveHowever men cannot live by higher knowledge alone. We need material knowledge to navigate through the material world successfully before we realize the value of higher knowledge and prepare ourselves to achieve it.

We need to experience life in all its hues and colors and perform our obligatory duties as expected of us to be qualified for progress in the spiritual plane. Salvation cannot be gained by escaping from the challenges of life, but through a process of inner transformation that can happen only when we face them and learn to deal with them suitably.

We need to learn the lessons that life has to teach us. We may read books, learn from others, live in a secluded place and contemplate upon the deeper aspects of life, but they are not as effective in our spiritual preparation as the knowledge that stems from direct experience. Hindu scriptures therefore advise men not to ignore the mundane and the ordinary in their zeal to pursue higher knowledge or self-realization. The following verse from the Isa Upanishad illustrate the point.Into deep darkness fall those who follow action and greater darkness those who follow knowledge alone.One is the outcome of knowledge, and another is the outcome of action. This is what we heard from the ancient seers who explained this truth to us.

He who knows both knowledge and action, overcomes death through action and attains immortality through knowledge.Into blinding darkness enter those who worship the unmanifest and into still greater darkness those who take delight in the manifest.Different indeed they declare what results from the manifest and distinct they say what comes out of the unmanifest. This is what we heard from the wise who explained these truths to us. He who understands both the manifest and the unmanifest together, crosses death through the unmanifest and attains immortality through the manifest.

Guru, God in Human Form Central to the traditional educational system of Hinduism is the concept of guru or teacher as a remover of darkness. A teacher is a god in human form. He is verily Brahman Himself.

Without serving him and without his blessings, a student cannot accomplish much in his life. In imparting knowledge, the teacher shows the way, not by trial and error, but by his own example and through his understanding of the scriptural knowledge, gained by his own experience, sadhana (practice) and deep insight. In ancient India, while the parents were responsible for the physical welfare of their children, a guru was responsible for their spiritual welfare.

It was his moral and professional responsibility to subject them to rigorous discipline and shape them into responsible adults. By keeping a close watch on his students and by not giving them any scope for leniency or carelessness, he ensured that they learnt by heart each and every subject he taught them. Till a student mastered a scripture completely and recited all the verses from memory without fault, he would not teach him another. In ancient India students were required to spend several years in completing their education, as they were required to learn every subject by heart and understand each and every verse thoroughly.

Once they mastered all the subjects to the satisfaction of their gurus, they were allowed to leave. After a student completed his education, his teacher had a right to demand a gift (gurudakshina) from him either in kind or in cash.In ancient India, two types of teachers taught children, namely acharyas and the upadhyayas. An acharya was considered superior to the upadhyaya for two reasons. He had both theoretical and practical knowledge, while an upadhyaya had only theoretical knowledge.

Secondly, an acharya lived in a gurukula and taught his students for free, besides undertaking the responsibility of looking after them by keeping them in their household. Thus he was both a father figure and a venerable teacher. An upadhyaya usually collected fee for his services, either working for an acharya or working for himself. Society therefore showed more respect to the acharyas and their students, because they valued the acharyas for not trading their knowledge for money and trusted their knowledge and experience more.

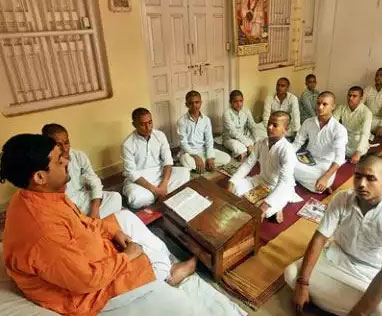

Another important concept associated with the pursuit of studies in ancient India was the gurukula system. A gurukula was a place where a teacher or a guru lived with his family and establishment and trained the students in various subjects. The gurukulas usually existed in forests, away from the buzz of the towns and cities. Admission into the gurukula was not as difficult as gaining the trust and confidence of the guru, without which a student would have to be satisfied with the basics.

A student had to serve his guru for years and convince him about his discipline, sincerity, desire, determination and level of intelligence, before he was given a chance to learn the advanced subjects.

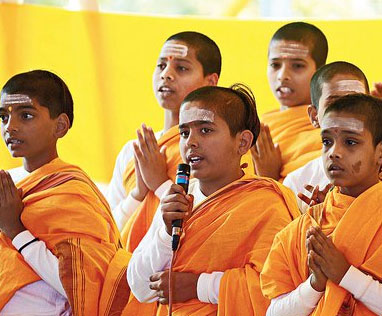

Life in a gurukula was hard. Students were subjected to rigorous discipline. They had to live in a very austere environment, practice celibacy and cultivate discipline and virtue, under the supervision of their master to gain his attention and confidence.

They were required to serve him personally and also undertake many menial jobs in his household to learn the virtue of humility and value the opportunity they had been given to learn under him. The gurus did not collect any fee for the services they rendered. But the students had to pay a heavy price by foregoing all comforts and subordinating their wills to those of their gurus. Each student was required to follow a rigorous routine, that really tested their grit.

Every day he had to wake up early in the morning, wash himself thoroughly in a nearby stream, do whatever work that was necessary in the teacher's household, recite the scriptures and then go out to beg for food. It was not teacher's concern to feed him, although he lived under his roof and served him. Even for begging, there were rules and restrictions. He was not allowed to beg from certain people and in certain places, such as those who were related to him or who were wicked or immoral or committed mortal sins; and in places that were impure and unclean.

He was not allowed to talk to women, eat certain types of food, or participate in singing and dancing, or use makeup or ornaments. He was not allowed to sit in front of his guru, unless asked or show any sign of disrespect or carelessness towards him. He was required to show great respect to the members of his guru's household, even if they were younger than him in age, and maintain certain demeanor and distance from the women who lived there. On certain occasions, students were given holidays, such as the days marked as ashtami, chaturdasi, amavasya and purnima. Besides these, they also enjoyed some seasonal and annual holidays to celebrate festivals, onset of seasons or to mark occasions like eclipses or some celestial phenomenon.

Sometimes if a Guru traveled to other places, his students accompanied him. This generally happened when the Guru was summoned by a local ruler to perform some Vedic rites or enlighten him on some specific spiritual matter. A guru usually designated a successor to ensure continuity, in the event of his premature death or serious illness.The gurukula system provided an effective environment to children to educate themselves under the close supervision of their teachers, in an atmosphere of extended family relationships and sense of belongingness, serving them as a home away from their homes. The aim of each student in the gurukula was not pass time and get a certificate of learning from his teacher, but remember everything by heart and gain mastery of every subject they learned.

Because there were no written books and no libraries, they had to make sure that nothing was omitted and nothing was forgotten. The austerity of the environment and the rigorous discipline enforced by their teachers helped them focus their attention on the central purpose of their stay and channel their energies into the task of learning and building their virtues and faculties. Since a student lived in the house of his teacher, he had a great opportunity to observe his master closely and learn from his behavior and conduct.

He also had ample opportunity to exchange ideas with his fellow students and learn from them, as they all shared similar experiences and competed with one another to gain the attention of their master.The teaching method continued to be oral, even after writing was introduced, as the priestly class were reluctant to put the scriptures into writing and make them public. So the education system continued to be exceptionally memory intensive. Itsing, who visited India between 672 and 688 AD gave an account of how education was imparted in India during his visit.

A student stayed with his teacher in his house and served him well till he became proficient in the subjects he was taught. The teacher ensured that the student missed nothing while learning. For every bit of knowledge received, the student was expected to provide an explanation or commentary to the teacher to his complete satisfaction. If the student faltered or failed to explain, the teacher made sure that he repented for it and corrected himself by learning again. The student was required to serve his teacher. He massaged his body, washed his clothes and sometimes swept the floors in the house and the yard.

However, if the student fell sick, the teacher took care of him. He gave him medicine and treated him like he was his son.Rabindranath Tagore, who was dissatisfied with the western model of education introduced into India during the British rule and the emphasis it placed on learning English language and the western subjects, felt that the gurukula system had several merits and could prove useful in educating the children of India in natural surroundings and building their character and sense of appreciation. He wrote," My view is that we should follow the ancient Indian principles of education. Students and teachers should live together in natural surroundings, and the students should complete their education by practicing brahmacharya. Founded on the eternal truths of human nature, these principles have lost nothing of their significance, however, much our circumstances might have altered through the ages."

He also felt the need to protect children from disturbing influences, a problem which the gurukulas took care in ample measure. He wrote, "The human mind is in the embryo stage in childhood and school boys should live in surroundings which protect them from all disturbing forces. To acquire strength by absorbing knowledge both consciously and unconsciously should be their sole aim, and their environment should be adapted to this purpose."

It was a highly centralized system in which the authority of the master was final. Since most of the teaching was secretive, there were no guarantees that the master was teaching the right and correct knowledge. * It was a caste based system, in which students of particular castes only were allowed.

Its emphasis on caste proved detrimental in the long run. It rendered Hindu society weak and divisive and contributed to its decline in the medieval period. * Girls were not admitted into gurukulas. They was meant exclusively for the male students. A few girls, however, managed to receive limited education either from their parents or from their husbands within the four walls of their homes. * It was based on rigid adherence to the scriptures, tradition and unconditional submission to the teacher.

It was also memory intensive. So there was little scope for creativity, experimentation and scientific temperament. * It was an excessively austere system, in which parents had little say and almost no control.

In the gurukulas, the teachers treated their students like their children. They gave them full attention and taught them every subject completely, without hiding any part. They exercised great patience as the young minds struggled to comprehend complex ideas. They also took their teaching seriously.

If the students faltered or became slack or showed any signs of moral turpitude, they took it upon themselves as their moral and obligatory responsibility to correct them and put them on the right path. As a parental figure, a guru had all the moral and scriptural authority to punish his students to the best of his judgment in whatever manner that he felt was appropriate. The punishments were usually light.

Gurukulas were not the only educational institutions in ancient India. Vocational education in professions such as carpentry, jewelry, metal works, stone carving, cattle breeding, agriculture and sculpture was often taught to children by their own family members or the heads of the family.

Some times the local guilds, which served as professional associations and financial institutions for the guild members, acted as training institutions or arranged for the training of their members. Sometimes, children worked as apprentices under their more senior family members, in their workshops, and perfected their skills. Knowledge was also imparted by wandering teachers, known as Charakas, who traveled from place to place and spread knowledge among people. We do not know how they taught.

Probably they held training camps or public discourses, where people could perfect their knowledge by seeking clarifications or learning new things or improving their existing skills. In addition, kings like Janaka often held religious conferences, to which they invited many scholars from various parts of the subcontinent. People who participated in them had a great opportunity to interact with other and learn from them. Those who completed their education in a gurukula, also worked as apprentices for sometime under experienced professionals, before they went on their own.

In ancient India education stretched over a period of several years, if not for decades. Manusmriti suggests a period of 9 to 36 years for the successful completion of education in a gurukula.

For the students, therefore, learning was a long and arduous journey, in which they had to cover a wide range of subjects and topics to meet the expectations of their parents and teachers. Religious learning required the study of either the smritis such as the Vedas or the srutis such as the Dharmashastras, the Vedangas, the Darshanas, the Puranas and so on or both. Students, who specialized in the Vedas, were referred as Vaidikas and those who specialized in the sastras, such as the law books and the Vedangas, were called Sastrins. Some students devoted their whole lives for the study of the scriptures.

They were called Naishtikas. Some students focused mostly on theory and were known as vidya-snataks. Some focused on practice and referred as vrata-snatakas. Those who engaged themselves in both were referred as vidya-vrata snatakas. Vocational education covered knowledge and skills specific to each vocation. Some knowledge was imparted secretively, only to qualified students, under an oath, either for reasons of competition or under the belief that free dissemination of such knowledge would be harmful to society or misused. Some important vocational courses of the period were:

* Brahma vidya, knowledge of Brahman, * Sarpa-vidya, knowledge of snakes, * Kshatra vidya, knowledge of the weaponry and martial arts, * Tantra vidya, knowledge of the chakras and energies. * Bhuta-vidya, knowledge of spirits and animals * Alchemy conversion of base metals into gold * Ayurveda, knowledge of medicines * Jyotisha, astrology * Nakshatra-vidya, astronomy * Pasu-vidya, cattle breeding, rearing, branding etc. Also included in the list were stone-carving, wood carving, metallurgy, weaponry, elephant taming, political science, knowledge of trade and commerce and so on. The Arthashastra of Kautilya mentions the subjects which a king has to be proficient.

Ancient India had a number of learning centers, where not one but several teachers lived and taught a wide range of subjects to groups of students, who came from far and wide. These were academic institutions of high standards, maintained and managed by men of eminence and experts in various fields.

The emergence of Jainism and Buddhism, the migration of people to towns and cities, the formation of large empires, contact with foreigners and the growing complexities of urban life, contributed to this development. Takshasila, Kasi and Nalanda were some of the important centers of learning of this period. Takshasila was the capital of Gandhara, in present day Afghanistan. It was a great center of learning, to which men from different parts of the subcontinent went either to teach or to learn.

Even the princes were eager to go there to learn the secrets of governance and martial arts. Chankya, the legendary minister of Chandragupta Maurya, lived and taught in Takshasila. Many Buddhist scholars also frequented the place and participated in religious debates. Kasi was another great learning center. Men, who received education in Takshasila, often went to Kasi to open their own schools.

The Nalanda university, was perhaps the most popular and prominent of all. It is no exaggeration to say that even ancient Rome had nothing that would match its grandeur or extent of fame. Founded during the Gupta period, it was visited by both Hiuen Tsnag, the Chinese traveler, who came to India between 630 and 644 AD and Itsing, who came a few years later.

It is from their writings, apart from some inscriptions and archeological evidence, that we know about its greatness. According to Hiuen Tsang and Itsing, the Nalanda University was a great center of Buddhist and Sanskrit learning. It had several high-rise buildings, towers and turrets and even an observatory, all enclosed within a brick wall, built mostly by the grants received from various patrons, including the one by the king Blaputradeva of Sri Vijaya or Sumatra. The college buildings stood in rows. There were libraries that went by such names as Ratnaranjak and Ratnodadhi.

At the height of its glory, the university had 10000 students who came from as far away as Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Ceylon and Tukhara. The teachers also came from different parts of the Buddhist world. Students had the opportunity to study a wide range of subjects like the Vedas, logic (hetu vidya), phonetics (sabda vidya), grammar (vyakarana), medicine (chikitsa), Samkhya, Nyaya, Yoga and the Buddhist canon.

The university encouraged freedom of thought, through discussions and debates and exploration of ideas, raising above parochial thinking and religious bias. The students and teachers belonged to a wide spectrum of religious beliefs and spent their time fruitfully exchanging ideas, mastering the scriptures and testing their concepts in debates and discussions. Hiuen Tsang, who spent some time within the university premises, proudly claimed to have defeated several scholars and put them to shame, including one from the Lokayata (materialistic) school.

Admission into the university was difficult, as it was based on previous academic excellence. The university was not meant for beginners, but for students seeking advanced studies only. To be admitted into the university, students had to pass an entrance examination, which was so difficult that hardly 20% passed. The university had its own administrative body to govern its affairs. It also owned agricultural lands and dairy farms, donated by various people, from which it received cart loads of rice, vegetables and milk. The university flourished for nearly 500 years before it lost its glory and prestige. Ruins of the ancient university can still be seen in Bihar, India.Education of Women Girls were not admitted to the Gurukulas.

They were not allowed to study outside their homes. However there were some educated women in ancient India, like Gargi and Maitreyi, who were generally relations or wives of some famous sages and kings. They received their education from their fathers or their husbands, who happened to be scholars or teachers themselves. Such was the fame of Gargi that she was invited by king Janaka to attend a religious conference. But it is doubtful if ordinary women in ancient India had any role other than performing household duties and raising children.

Education of Lower Castes Lower caste people were explicitly prohibited from the study of the Vedas. They were not permitted to study any subject outside their occupation. Manusmriti prescribed severe punishment not only for the lower caste men, who dared to study the Vedas, but also those who dared to teach them. In the early Rigvedic period, some sages were broadminded enough to admit low caste children as their students, as is evident from the story of Satyakama Jabala who was born to a free woman and Yajnavalkya who came from a very humble background. But the trend changed completely during the later Vedic period, so much so that even the mere act of hearing the Vedic hymns by low caste men was declared a sacrilege and great crime.

Students were specifically warned in the Smritis not to recite the Vedas in unclean places where the low caste people lived. The priestly families, who had access to the knowledge of the Vedas, wanted to keep it a secret for ever, so much so that even after writing was introduced, they preferred not to render the scriptures into writing and keep their teaching oral in order to limit the possibility of their free circulation.

The story of Ekalavya from the Mahabharat illustrates how the lower castes were subjected to shameless discrimination by higher castes to prevent them from acquiring knowledge that would threaten their superiority and monopoly. The original idea was that religious knowledge should not be imparted to people who were impure or unclean. But as the time went by all the lower caste people were categorized as impure and disqualified from learning.

However, this was a problem specific to the vedic society. Outside the vedic fold, people from all wakes of life had an opportunity to go to schools and learn. Buddhism, Saivism and several ascetic traditions scoffed at the very idea of caste based distinctions. They disregarded the caste rules and allowed people from all wakes of life to participate in religious events and acquire knowledge through study and service.

Hinduism recognizes the importance of personal experience in arriving at truth. It regards the external world as a great illusion and any activity concerning it as a part of that illusion only. Hence the traditional view that all theoretical knowledge is but inferior and unworthy. However it does not discourage those who want to acquire it as a part of their obligatory duty or exploration of truth.

It is also not averse to scientific pursuit of knowledge, so long as such pursuit is in harmony with the spiritual aims of man and based on the principles by which one can arrive at any truth. While it acknowledge the value of knowledge, be it higher or lower, it is also wary of the fact that you cannot teach everything to every one. Knowledge should be imparted only to those who are interested in it, who are mentally disposed towards it, who are qualified by virtue of their current knowledge and degree of discipline to receive it.

Teaching sensitive knowledge to an unqualified person is therefore dangerous. It is like giving a knife to a monkey, which does not know how to use it correctly and in the process of toying with it may even hurt itself. It should be imparted to only those who know how to use it correctly for their own welfare and that of others. We find a similar approach in the Bhagavadgita, in which Sri Krishna says," This (the Bhagavadgita) should not be spoken to the one who is not austere, who is not My devotee at any time, who does not want to serve Me, and who is envious of Me.